Introduction

Rights of Women was formed in 1975 as a direct response to the fifth demand of the Women’s Liberation Movement for legal and financial independence for women. A group of women legal workers founded the organisation to help women find their way around the many man-made laws that affected them.

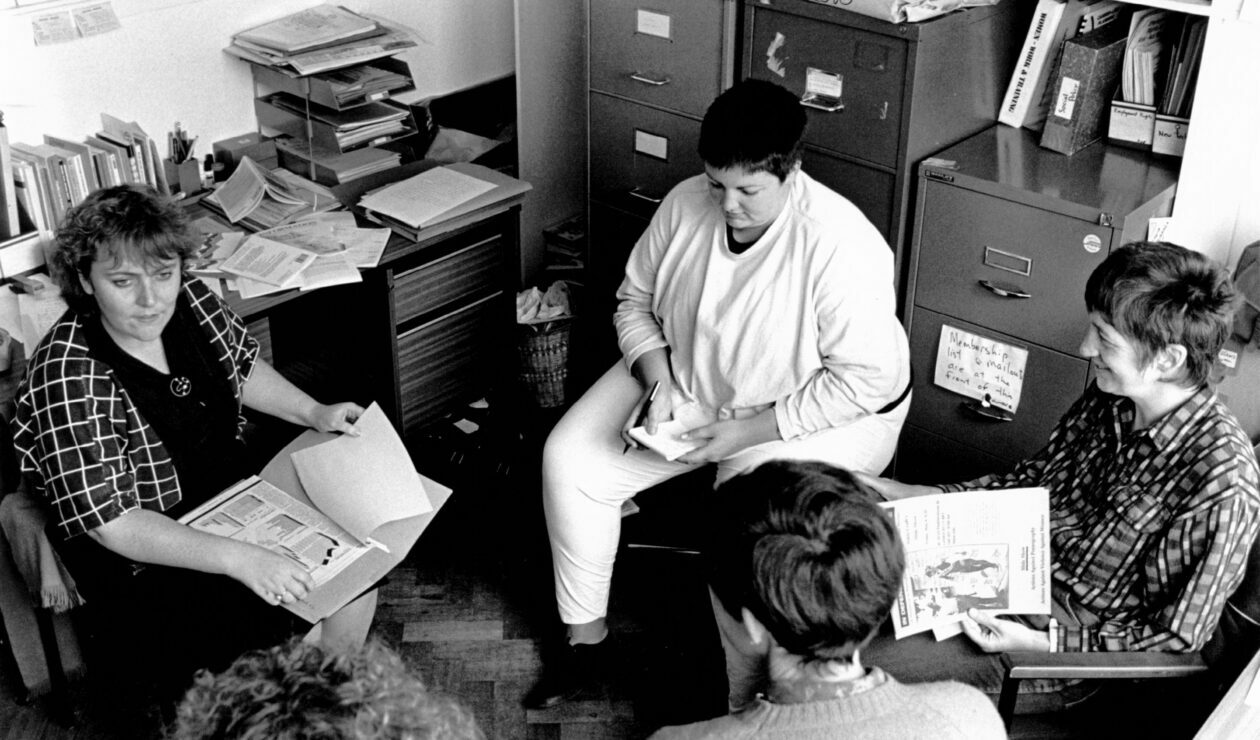

Shortly after finding premises, we set up the legal advice line for women. As the only feminist legal project in the UK at the time, we networked with feminist lawyers and activists and with women’s organisations both nationally and internationally.

Over 40 years our services have developed and provided many thousands of women with free legal advice and information to increase their access to justice and campaigned for changes in the law which protect women from violence and discrimination.

2015 marks our 40th anniversary and an opportunity to reflect on the work of the organisation over those 40 years and to celebrate our achievements and some of the women who have been involved in our work.

We explore some of the campaigns and issues that we have worked on and the developments in law and policy which have resulted and celebrate some of the women who have made that work possible.

We would like to say a very big thank you to our pro bono researchers from Dechert LLP, Annabelle Nellson, Rachel O’Neill and Emma Ward, who put so much time and effort into making these herstory pages possible.

Women's Equality

In the late 1970s, we campaigned as part of the YBA Wife campaign aimed at raising awareness of the discrimination married women faced. At that time, for example, women were unable to claim social security benefits in their own right.

As a key part of our campaign, we lobbied for

- Individually based benefits

- The abolition of the married man’s tax allowance

- Dependency increases to be paid to married women

To achieve this, we consulted with a wide range of groups, protested outside the Department of Health and Social Security and in 1984 our members present a stale loaf of bread to the Secretary of State with the message: we are fed up with being fobbed off with crumbs from under men’s tables – we want an independent income for women.

We also campaigned for occupational pension rights on divorce, with the aim of preventing women from losing their occupational pension schemes on divorce with no compensation. In 1985, we responded to the Lord Chancellor’s Department consultation paper on Occupational Pension Rights on Divorce.

Much of what we campaigned for has since been achieved. The Welfare Reform and Pensions Act came into force in 1999 and allowed occupational and personal pensions to be shared between couples on divorce. Husbands and wives are not taxed separately and the married man’s tax allowance was eventually abolished in 2010. The Government announced changes to the social security system in the Social Security Act 1990 and entitlement to supplementary benefits now depend on a set of prescribed conditions rather than on sex or marital status. People who are married or cohabiting still cannot claim means-tested benefits separately from their partner but now either one of them can be the claimant, rather than it automatically being the man.

In 1991, we started campaigning on the Homicide Act 1957 and in relation to the treatment in the criminal justice system of women who had killed their violent partner. Specifically our work focused on the partial defence of provocation. By providing a partial defence where the response to provocation is caused by a “sudden, temporary loss of control”, the defence favoured men who react in violent anger over women who kill with premeditation from fear rather than rage. We argued that this was inappropriate in cases involving domestic violence.

During the 1990s we worked with Justice for Women and Southall Black Sisters on the high profile cases of women including Emma Humphreys, Sara Thornton and Kiranjit Ahluwalia.

As a result of these cases, the law on provocation as a defence for murder was changed and the idea of cumulative provocation is now more widely understood and applied. However, we continued to express our concern about the application of the law in our response to the Law Commission’s consultation on partial defences to murder in 2004 and held an event to discuss this with activists and lawyers in the same year.

Lesbian Parents

Our Lesbian Custody Group was established in 1982 to provide support for lesbians who were experiencing discrimination in the family courts. In November 1984, the project launched its report Lesbian Mothers on Trial which included a survey of 36 lesbian mothers’ experiences of the legal system on separation and divorce between 1974 and 1984. Our research found that lesbian mothers faced prejudice and were assumed to be unfit and unsafe parents and that children would experience harm in their care. The report highlighted that this discrimination was at all institutional levels within the judiciary, welfare officers, and the legal profession.

We trained family lawyers on how to represent lesbian mothers in child custody cases and provided a legal advice and support service for lesbian mothers. In 1986, the report was incorporated into a book, The Lesbian Mothers Legal Handbook which included a critique of the law and provided strategic advice to lesbian mothers for dealing with lawyers and court welfare officers. We also made use of the media to promote positive images of lesbian parenting.

As a result of the work of The Lesbian Custody Group and the wider feminist movement campaigning for lesbian rights, the case law began to change during the second half of the 1980s and it was no longer assumed that lesbians were unfit mothers. Although levels of prejudice experienced in the courts were still unacceptable, increasingly lesbian mothers were being granted custody of their children.

Subsequent legislation including the Civil Partnership Act 2004 and the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 have created new legal recognition of lesbian couples including rights in relation to children.

We continue to support lesbian mothers with advice and information on our advice line and with our Guide to Lesbian Parenting.

As part of our work on lesbian parenting we campaigned to oppose section 28. In December 1987 clause 27 of the Local Government Bill was introduced to prohibit local authorities from promoting homosexuality, teaching the acceptability of homosexuality as a “pretended family” relationship in schools or giving financial or other assistance to any person for these purposes. Clause 27 of the Bill subsequently became law as Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988.

Our Policy

Group and Lesbian Custody Group wrote a briefing paper opposing Clause 27, entitled “Outlawing the lesbian community”. We organised a march of more than 12,000 gay men and lesbians to protest against Clause 27. Lesbians involved in the Lesbian Custody Group played an active role in the wider campaign by speaking at meetings, participating in TV discussion programmes, interviews and briefing Parliamentarians.

Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 was finally repealed in England and Wales in November 2003.

Family Justice and Domestic Violence

Domestic violence was still not seen as a problem in relation to child contact. A lot of judges in the early 80s were not convinced of its existence, its seriousness

In 1997, our Best Interests campaign was set up in response to the experience of women in the family justice system. The Children Act 1989 required the courts to prioritise the best interests of the children in decision-making and yet women were experiencing a presumption of contact in favour of fathers even where domestic violence was an issue.

We fought for recognition of the harmful impact of domestic violence on children in residence and contact disputes following the implementation of the Children Act. As part of the campaign, we lobbied MPs and submitted evidence to the Family Law Commission.

We published a research report Contact between children and violent fathers: in whose best interest? highlighting concerns about the response of the family justice system to domestic violence. Mothers in child contact proceedings felt that their views about the risks to themselves and their children were marginalised by professionals in the family justice system. The purpose of this report was to challenge the idea that contact with a non-resident parent is almost always beneficial for a child and (at that time) thought to be supported by research that children do better after separation if they are able to maintain a good relationship with both parents. On this assumption, a firm presumption in favour of contact with fathers was applied by the Courts before the Children Act was implemented and reinforced by the Court of Appeal.

Although the Best Interests campaign was partially successful in changing family law legal guidance, the family courts still rarely denied contact to violent perpetrators. Since 1997, there have been significant developments in the law and policy on domestic violence and child contact, yet anecdotal evidence from our family law advice line indicates ongoing failures and missed opportunities within the family justice system to protect women and children from violent ex-partners and a tendency of judges and other statutory professionals to minimise domestic violence in the context of child contact.

In 2011 the Family Justice Review described the family justice system as not operating “as a coherent, managed system. In fact, in many ways, it is not a system at all.” It is a family justice system that our research and the experience of our advice line callers has shown continues to let women down.

In 2012, in partnership with the Child and Women’s Abuse Studies Unit at London Metropolitan University, we undertook a further research project looking at women’s experience of child contact and domestic violence in the family justice system. In the years between our Best Interests campaign and 2012 there had been significant developments in law and policy. The decision in the case of Re L in 2000 set out guidance for judges to follow in making decisions about contact between children and their violent fathers. The definition of harm in the Children Act 1989 was amended to include a child seeing or hearing domestic violence in 2004. Further guidance to judges was issued in Practice Direction 12J.

Yet the findings of this research published in a report, Picking up the pieces: domestic violence and child contact, echoed the experiences of the women we spoke to as part of our Best Interests campaign.

Our recommendations included the introduction of a more robust and statutory framework within the family justice system to ensure the early identification of and effective response to women and children’s experiences of domestic violence, the protection of victim-survivors from direct cross-examination by their perpetrators and from contact with them inside court buildings and monitoring by Government of the impact of the legal aid cuts and outcomes in private Children Act proceedings where domestic violence is a feature.

We hoped that the Family Justice Review would be an opportunity to include these recommendations in the significant changes which were to come. However, driven by an expressed desire by the Government to speed up decision making in family cases and improve processes but undoubtedly along linked to an agenda of budget cutting in the Ministry of Justice, April 2014 saw the introduction of wholesale changes to family law and the family justice system which instead of improving women’s ability to access justice, have made it much, much harder. The introduction of the Child Arrangements Programme and legislative changes to judicial decision making in the Children and Families Act 2014 give women affected by violence fewer opportunities to have their experiences of violence heard.

Our work on this vital issue for women continues and in 2015 will publish a new handbook, Child arrangements and domestic violence: a handbook for women, aimed at supporting women, many of whom find themselves unable to access advice and representation and are representing themselves in proceedings.

Violence Against Women

In 1990, we led various campaigns to improve the law on domestic violence. We responded to the Law Commission’s Working Paper 113, Domestic Violence and Occupation of the Family Home. Whilst our overarching aim of our work has been to end male violence against women, during the 1990s we advocated for a more coherent legal framework of civil remedies, sanctions in criminal law and related aspects of immigration law, housing and legal aid provisions to ensure all women had access to personal protection and safety from their violent partners.

The Family Law Act 1996 introduced civil law remedies for protection from domestic violence: non-molestation and occupation orders. The Domestic Violence Crime and Victims Act 2004 broadened the availability of those protections to include same sex and cohabiting couples and made breach of a non-molestation order a criminal offence. In 2000 we published the first edition of our Domestic Violence DIY Injunction Handbook and begun delivering training to professionals on how to support women to apply for these new remedies.

In 2003, we held a conference Violence Against Women: Challenges within the Law looking at violence against women in its many forms and how the law dealt with domestic violence, rape and sexual violence, forced marriages and honour killings.

In 1981 we began campaigning for the criminalisation of rape in marriage. The campaign aimed to assert women’s right to refuse to have sex with men in all situations, to criminalise marital rape and to remove bias which existed against women in legislation, legal procedures and police practice in relation to rape and sexual assault.

The campaign followed the public outcry at the Morgan case in 1976 where it was held that a man was not guilty of rape if he had an honest but not reasonable belief that the woman consented.

As part of our campaign we:

- Provided submissions to the Criminal Law Revision Committee

- Worked with Women’s Aid, Rape Crisis and Women against Violence against Women to raise awareness of the issue of marital rape

- Worked with MPs and other organisations to make amendments to the criminal justice process to improve it for women

After campaigning on these issues for a decade, the courts of England and Wales recognised marital rape as a crime in the landmark case of R v R on 23 October 1991. Lord Lane in his judgment confirmed

“The idea that a wife consents in advance to her husband having sexual intercourse with her whatever her state of health or however proper her objections, is no longer acceptable.”

The Home Office also issued guidelines about the need to improve the police treatment of women who have been the victim of rape.

During the 2000s our work on sexual violence intensified. By 2005, we had published the first edition of From Report to Court: a handbook for adult survivors of sexual violence and in the same year launched a new dedicated advice line for women affected by sexual violence.

We continue to work with Government, the Police and Crown Prosecution Service in relation to the criminal justice system’s response to women who have experienced rape by a partner or former partner. As a member of the Crown Prosecution Service’s Violence Against Women and Girls External Consultation Group and Community Accountability Forum we continue to raise concerns about the low conviction rates for rape and sexual offences and women’s experience of the criminal justice system.

n 2007, we held a conference BMER Women, the Law and Violence – Where’s the justice? conference which examined the law, legal rights and remedies available to black, minority, ethnic or refugee (BMER) women including women seeking asylum and experiencing violence. The focus was on the fact that women experiencing violence were being marginalised and denied access to justice.

You can read the report from this conference here.

At this conference, our publication, Pathways to Justice: BME women, violence and the law was published. The handbook for professionals explored the legal remedies available to protect BME women in the family, criminal and immigration law systems.

We have continued to work closely with specialist women’s organisations on forms of violence including harmful practices such as forced marriage.

In 2005 we responded to the Government consultation on the criminalisation of forced marriage. In our response, we rejected the proposed creation of a new criminal offence of forced marriage. This rejection was based on the experiences of women and girls affected by forced marriage and the expertise of our sister organisations in the BME women’s sector including Imkaan, Southall Black Sisters and Ashiana. We argued instead for the creation of a new civil law remedy and worked closely with Lord Lester on the development of new forced marriage protection orders

In 2013 the Coalition Government consulted again on the criminalisation of forced marriage and despite a reiteration of the opposition expressed in 2005, a new offence was introduced in 2014.

In 2015, in partnership with Imkaan we published “This is not my destiny”. Reflecting on responses to forced marriage in England and Wales. This project explored the effectiveness of both civil and criminal law remedies for forced marriage and combined made a series of recommendations for the improvement of the response to women and girls at risk of forced marriage.

In 2009, working with the Demand Change! campaign, we coordinated a coalition of about 70 organisations campaigning for a new criminal offence of paying or attempting to pay for sex with someone who has been controlled for gain. Our expertise in and understanding of the application of the criminal law were called upon by those supporting the legislation through Parliament. Working closely with Fiona Mactaggart MP we were directly involved in the drafting of the proposed new offence and in lobbying members of both Houses.

Our lobbying and campaigning efforts were successful and section 14 of the Policing and Crime Act 2009 received royal assent in November 2009. Section 14 opened up the debate on prostitution, focusing attention on those who buy sex and deterring them from doing so. A man who is not deterred and who buys sex from a woman who has been forced to sell it by a trafficker or violent pimp risk prosecution.

You can read more about the campaign in briefings on the offence here.

Despite challenges in the implementation of the new offence, we believe that the creation of this new offence is a very important step towards recognising prostitution as a form of violence against women and to raise awareness of the devastating impact it has on women.

Women's Rights and Human Rights

In 2000 we held a national conference, Women’s Rights are Human Rights.

In 2010, we published a research report Measuring up? UK Compliance with international commitments on violence against women in England and Wales addressing specifically how the UK government is addressing its commitments to international human rights mechanisms.

Whilst welcoming the then Government and Welsh Assembly Government’s commitments to and strategies to address violence against women and girls (VAWG) and acknowledging that the UK is signed up to all major human rights treaties, our report analysed key areas where more needed to be done to address VAWG. We called on the Government to withdraw reservations to CEDAW restricting the rights of women with an insecure immigration status and to ratify Protocol 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The report also highlighted areas of law and legal policy which continued to fail to meet the needs of the most disadvantaged women, citing in particular the treatment of women in the immigration system.

In 2014 we contributed to the UK shadow report to the CEDAW committee, contributing in particular to chapters on legal aid and access to justice and family law and continue to work with other women’s organisations including the Women’s Resource Centre in the preparation of a further shadow report in 2015.

We continue to call on the Government to protect women’s rights within our international human rights frameworks and in particular to ratify the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (known as the Istanbul Convention).

Legal Aid

Women’s access to justice has been central to our work across the decades and key to that has been the availability of legal aid.

In 2002 we published research, Access to Justice: A report on women’s access to free legal advice in Hackney, Haringey, Lambeth and Tower Hamlets, which found that women experienced particular barriers to accessing free legal advice particularly women for whom English is not their first language, disabled women and women with dependent care responsibilities. A lack of awareness of the availability of schemes and services providing advice compounded the vulnerability of those women.

Proposals in the Law Commission’s Consultation Paper, A New Focus for Civil Legal Aid concerned us greatly in 2004. If implemented we believed the proposed changes to the legal aid scheme would impact disproportionately on women. You can read our response to the consultation here. This was the subject of discussions at our seminar, Crisis? What Crisis? The Deepening Crisis in Legal Aid and its Effect on Access to Justice for Women in March 2005.

In 2011 we responded to the new Coalition Government’s proposals for further reform of the legal aid scheme with a research report Women’s Access to Justice, which found an urgent need to retain and rebuild the legal aid scheme if women were to have necessary access to legal advice and representation in civil law proceedings.

During a long campaign we worked alongside the wider campaigns to protect the legal aid scheme from the deep cuts proposed by the Government led by Justice for All and the Law Society’s Sound off for Justice campaign. We worked closely with Parliamentarians in both Houses, gave evidence to the House of Commons Select Committee on Legal Aid, met with Ministers and civil servants from the Ministry of Justice and protested outside Parliament.

Our campaign achieved important victories during the passage of the Bill. Our lobbying ensured that the cross Government definition of domestic violence was included in the Act and the broadening of the domestic violence evidence gateway to include evidence including referral to a Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference and reports from health professionals.

However, despite these important victories, the cuts to the legal aid scheme introduced in April 2013 have had a devastating impact on the women who contact our services and our partner organisations.

A year after the implementation of the Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) and the domestic violence evidence gateway criteria for family law legal aid, our research report Evidencing domestic violence; a year on demonstrated that the new legal aid regulations were denying access to safety and justice to the very women whom the Government expressly sought to protect from the removal of family law from the scope of the legal aid scheme.

The Government repeatedly promised to protect legal aid for those affected by violence. In February 2013, a new Cross Government definition of domestic violence and abuse was introduced, extending this to expressly include controlling and coercive behaviour. Yet not two months later with the implementation of LASPO in April, the strict evidence requirements of the legal aid regulations make it difficult, if not impossible, for women to evidence those very forms of abuse. The regulations also fail to acknowledge the often life-long risks of violence by placing a two year time limit on most of forms of evidence.

For this reason we issued judicial review proceedings against the Secretary of State for Justice. Our claim specifically challenged the lawfulness of regulation 33 of the Civil Legal Aid (Procedure) Regulations 2012 made under section 12 of LASPO. We argued that the evidence requirements set out in regulation 33 are ultra vires LASPO as they substantially narrow the statutory definition of domestic violence in the Act.

In a devastating judgment for survivors of domestic violence in January 2015, Mrs Justice Lang found that the Lord Chancellor had not exceeded his powers under LASPO in creating the evidence criteria. However, she acknowledged the weight of evidence presented that the criteria creates a bar to family law legal aid to those affected by domestic violence.

I am satisfied that the Claimant has shown a good arguable case that some victims of serious domestic violence, who are genuinely in need of legal aid, cannot fulfil the requirements of regulation 33. Typically, victims are excluded in circumstances where serious domestic violence led to a complete breakdown of the relationship.

Then, more than 24 months later, there is an application by the perpetrator of the violence for contact with a child of the family, or going contact arrangements break down. By the date of application for legal aid, their evidence of domestic violence is older than24 months, but they remain fearful of their former partner.

Despite the disappointment of this judgment and following lobbying from ourselves and other women’s and legal organisations in July 2015 a further amendment to the regulations was introduced which ensures that a woman’s legal aid certificate, and therefore her access to legal advice and representation, will not end when her evidence of domestic violence becomes older than 2 years.

Appeal

Nearly three years on from and to coincide with our appeal against the High Court’s judgment on 28 January 2016 we published another in our series of research reports Evidencing domestic violence: nearly three years on which continued to demonstrate that nearly 40% of women experiencing domestic violence could not produce the required evidence to apply for family law legal aid.

On 18 February 2016 judgment was handed down in our appeal and regulation 33 of LASPO was ruled unlawful. In his judgement Lord Justice Longmore said

Legal aid is one of the hallmarks of a civilised society.

I would conclude that … regulation 33 does frustrate the purposes of LASPO in so far as it imposes a requirement that the verification of the domestic violence has to be dated within a period of 24 months before the application for legal aid and, indeed, insofar as it makes no provision for victims of financial abuse.

Read the judgment here

Immigration and Asylum

From the 1990s we worked with other women’s organisations including Southall Black Sisters to abolish the One Year Rule (OYR) which required migrant women who came to the UK in order to join their British or settled husband to stay in their marriage for at least one year before they could apply to remain in the UK permanently. By leaving their partner before the one year period, women lost their right to remain in the UK. Even if the woman completed the one year period, any application for leave to remain thereafter had to be supported by both parties. This resulted in women being trapped in violent relationships which they could not leave for fear of being removed from the UK. Furthermore by reason of the OYR they were not entitled to access welfare benefits.

The main aims of the campaign were to:

- Abolish the OYR;

- Allow rights of appeal to women subject to the OYR who left marriages and were refused rights;

- Recognise the impact of domestic violence in the context of immigration law and take this into account in dealing with applications to remain in the UK; and

- Abolish the “no recourse to public funds” rule (which meant that women were forced to stay in relationships because they were economically dependent on their husbands and had no right to state support).

Following our campaign, the Home Office introduced a concession in 1999 which enabled victims of domestic violence to apply for indefinite leave to remain before completing the one year period.

Despite the concession it was still evidentially difficult for women to prove to the satisfaction of the Home Office that they had been subject to domestic violence and so we continued campaigning with Southall Black Sisters and other organisations regarding the evidence requirements for proving domestic violence. In 2002 the Home Office accepted our call and broadened the permitted forms of evidence to include evidence such as reports from domestic violence support organisations.

The concession was eroded when in 2011 a requirement was introduced that people needed to demonstrate they had no unspent criminal convictions in order to get indefinite leave to remain. This requirement affected women who had been falsely accused of crime by their abusive partners or had been convicted of an offence after defending herself from harm. Following our successful campaign work alongside Southall Black Sisters and other organisations this requirement was abolished in 2012.

Working closely with Southall Black Sisters and Amnesty from 2007 we campaigned to end the “no recourse to public funds” rule (NRPF). The rule prevents people subject to immigration control including spouses, from accessing certain welfare benefits such as income support and housing benefit as well as housing and homelessness assistance. This had a particularly devastating impact on women fleeing violent relationships and making an application for indefinite leave to remain under the domestic violence rule. It left them unable to access housing benefit for the purpose of staying in a refuge or other benefits to feed and clothe themselves and their children.

As a result of the campaign, in 2009 the Government piloted a scheme to provide temporary relief to women subject to the NRPF rule who were facing domestic violence. The pilot was delivered by Eaves and enabled women who were in the UK on a spousal visa to flee their abusive relationship and obtain financial support and accommodation. The pilot resulted in a concession to the NRPF rule for women on spousal visas who were fleeing abusive relationships. The Destitution Domestic Violence Concession, which remains in force today, continues to provide the financial support needed to ensure women on spousal visas who flee their abusive relationship do not face destitution. You can read more about this in our guide Domestic violence, immigration law and “no recourse to public funds”.

This protection only apply to women who are in the UK on spousal visas. We continue to campaign as members of the NRPF campaign group and members of the Under-represented Group at the Home Office both on the abolition of the NRPF condition for vulnerable women who have experienced violence as well as the broadening of the Destitution Domestic Violence Concession to include women in other immigration categories such as dependents of workers and students, and family members of EEA nationals to prevent them from becoming destitute after fleeing abusive relationships.

We also continue to support Asylum Aid’s Charter Group and their recent campaigns to eliminate discrimination in the asylum system. We sit on the equality sub-group of the National Asylum Stakeholder’s Forum and continue to campaign on relevant issues such as improving support available to asylum-seeking women experiencing domestic violence.

One of our most recent areas of campaigns and policy work is around migrant women’s access to justice in light of the impact of legal aid cuts. We have spoken at conferences on these issues and will continue to campaign on this issue which remains of serious concern.

Women

Jenny Earle became our first paid Project Officer in 1977 and later our Coordinator.

My work focused on campaigning for women’s rights with a bunch of very dynamic and committed feminists, churning out leaflets and newsletters, recruiting volunteers and setting up the advice service. It was very high energy and exciting. There were lots of battles to fight and we got stuck in.

Jenny worked on our campaigns for women’s financial independence and supported women to bring claims under the new Sex Discrimination and Equal Pay Acts. Then, she went on to train as a solicitor.

It seemed like the logical next step – to be able to fight injustice fully-armed. I stayed involved as a volunteer throughout my training.

She now works as the Director of the Prison Reform Trust’s Programme to Reduce Women’s Imprisonment.

We do have more formal equality now but women are still massively disadvantaged and discriminated against.

Lynne Harne was our Research and Policy Officer from 1983 to 1985 when she was author of our 1984 research Lesbian Mothers on Trial and the Lesbian Mothers’ Handbook. She returned as Policy Officer in the mid 1990s and set up the Best Interests Campaign, campaigning on domestic violence and child contact. She remained a member of our Lesbian Custody Group and then Policy Group until late 1990s whilst working as an academic.

Family law does not recognise that women and children are disproportionately affected by male domestic and sexual violence and legal changes in terms of shared parenting and the welfare principle following separation have made matters worse for many women.

After leaving Rights of Women Lynne became an academic, teaching Women’s Studies and Social Policy and Criminology. Her research “Violent Fathering and the Risks to Children; The Need for Change” was published in 2011.

Lynne now works as an independent researcher and writer and continues her feminist activism.

Elizabeth Woodcraft was involved in our work between 1980 and 1995. As a family law barrister she volunteered on the advice line.

We advised on all sorts of issues on the advice line – divorce, child custody and access (as they were known then), maintenance, employment, immigration, crime, prostitution.

She delivered advocacy workshops for new women lawyers. Later she was a member of our Policy Group and Chair of our Management Committee.

I am proud of the way in which Rights of Women has always brought together political activism, academic research and publications and worked and continues to work with practitioners in the field.

Continuing to work as a barrister until her recent retirement.

I relied upon Rights of Women’s research Contact between children and violent fathers: In whose best interests in many of my cases. Domestic violence was still not seen as a problem in relation to contact. A lot of judges in the early 80s were not convinced of its existence or seriousness.

Liz is also a writer of crime and other fiction. Her novels Good Bad Woman and Babyface chronicle the life and work of barrister Frankie Richmond.

Keep campaigning, educating, asking the questions. Reminding women what is possible.

Pam Alldred was a member of the Lesbian Custody Group and our Policy Sub group from the early 1990s. She became a member of our Management Committee in 1994 and was our Chair between 1999 and 2003. During this time she oversaw an organisational review and our transition from a collective to management structure. Despite this change in structure Rights of Women remained committed to its feminist ethos and to providing services for women by women.

There was concern that mainstream organisations, such as Victims Support, were taking the majority of funding and weren’t going to meet women’s specific needs.or understand their particular support or protection needs.

Pam has remained a key supporter of Rights of Women. In 2013, as Director of the Centre for Youth Work Studies at Brunel University, she led a group of organisations from 4 EU countries including Rights of Women in work to address the skills and knowledge of professional working with children and young people on peer on peer abuse. As part of the project we delivered training and authored a publication, Understand, Identify, Intervene: Supporting young people in relation to peer-on-peer abuse, domestic and sexual violence.

Ranjit Kaur was our first Director from 2000 to 2007. Under her leadership our services were developed and our commitment to addressing violence against women was strengthened.

The issues we focused on were largely determined by the issues women shared on our advice line and our advice services developed substantially over the years.

Our specialist criminal law advice service for women affected by violence was established in 2005 and won the Lilith Award for best voluntary sector violence against women project. Ranjit ensured that the organisation focused on women’s rights as a human rights issue and on the particular needs of Black and Minority Ethnic women, organising our national conferences Women’s Rights are Human Rights in 2000 and BMER women and violence: where’s the justice? in 2007.

Since leaving Rights of Women Ranjit became a magistrate in Westminster and an equalities and management consultant.